On Wednesday 22 June 2022, the United Kingdom declared a national incident after vaccine-induced poliovirus was found in sewage samples in North and East London. Wild polio currently exists in only two countries—Pakistan and Afghanistan—and was declared eradicated in the UK in 2003. We are told that positive sewage tests have been found since February 2022, which would suggest that scientists are looking at a hypothesis of ‘ongoing transmission’ around the country.

But is polio the only unusual virus detected in the UK in the last six months, and was it entirely unexpected? Is it sheer coincidence that our very own MHRA is collaborating with the World Health Organisation's Polio Eradication Initiative and houses its polio laboratory at the heart of Britain's medicines regulation complex, at the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation?

Not surprising

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), in a March 2019 blog post written when the agency was still designated as Public Health England, warned that a resurgence of Victorian diseases was expected—and that is exactly what we appear to be seeing now, according to current press releases. Professor Mark Woolhouse, professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh, describes what we are seeing as ‘chatter’. ‘Chatter’ is the term regularly used by counter-terrorist officers (a not insignificant context, given that the UKHSA’s new name combines the concepts of public health and national security) to describe the small signals that may signify some more major calamity on the horizon. Infectious disease prevention works in much the same way as counter-terrorism. Currently, we are being alerted that ‘chatter’ is getting louder; perhaps this increased volume stems from the heightened awareness of the risks since Covid-19. Even though we have seen the world strengthen its security systems, the world’s best-known public health official, Professor Anthony Fauci, warns of a new ‘pandemic era’.

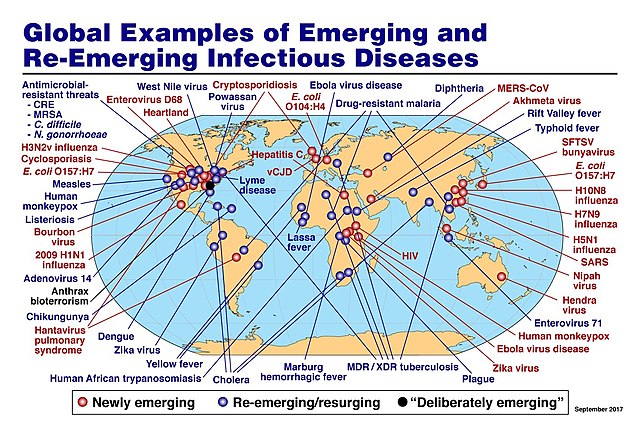

Scabies, rickets, scarlet fever, whooping cough, tuberculosis and typhoid fever, amongst others, are returning to Western nations—but not as we remember them. Some of these old terrors will return with a vengeance, as a new variant or strain. Will our old-fashioned belt-and-braces medications that we have come to rely on for so long be effective, if they even prove to be widely available? What is driving the spread of new, old and existing viruses—or is it simply that we are searching every corner of the planet expecting to track down the next pandemic—a case of seek and ye shall find? Perhaps we should brace ourselves, as the blame for resurgent infections is likely to be attributed in public discourse to a variety of reasons: climate change, population growth, rainforest destruction, intense farming, the increased trade in wildlife combined with the exponential rise in zoonotic disease.

As the United Kingdom has been extricating itself from the European Union, non-EU immigration has increased, with large numbers of people travelling to and from Africa and Asia. Despite a couple of years of draconian travel restrictions and Covid lock-ups (sic), travel is still always named as the biggest driver of disease importations. The recent outbreak of monkeypox has been linked to Nigeria, with many more cases attributed to music festivals, adult saunas and orgies around the world. The 2022 British polio outbreak is thought to have been derived from another country, one which still uses a vaccine containing a live weakened strain of the polio virus; this is why the health authorities are describing the strain of poliovirus that they have detected in London as ‘vaccine-derived’. The UK itself has not used this particular vaccine, the Sabin oral vaccine, since 2004; we have reverted to the injectable Salk vaccine for our polio immunisations.

Many would care to argue that polio has been given the perfect opportunity to reappear due to the Covid-19 pandemic, because of increased vaccine hesitancy and a major shift towards funding Covid-19 campaigns at the expense of other precious public health resources. Furthermore, disruptions to normal childhood immunisation schedules due to lock-ups, and a failure to provide face-to-face appointments with health professionals, will no doubt have contributed to the opportunity for polio. In the UK, vaccine administration to children has decreased in the past couple of years, especially in parts of London.

Over-informed

Pharmaceutical research is currently travelling at a million miles an hour, with ‘information cascades’ bubbling with details of the thousands of novel drugs currently in development. This massive volume of information is designed to confuse and overwhelm the general population. As genomic medicines travel down the brand new experimental pipeline at the speed of light, many will relax and participate in clinical trials from the comfort of their armchairs, and millions will come to expect and to rely on brand new drugs which will be delivered in record speed to their door (probably by drone). The norm will be a much shorter delay between demand and delivery. The 100 Days Mission announced by Britain, the vision of Sir Patrick Vallance and Melinda Gates, would appear to be the answer. To put that into context, until 2020 a clinical trial would take years in three back-to-back phases, up to a timescale of 3,652 days. The first Covid vaccine was delivered in 300 days.

Generic medicines that the majority of us are used to will start to disappear from pharmacy shelves. Novel ‘super-smart’ genomic medicines will replace them at alarming speed—but at what cost to our health? Does anyone supplying them actually care? Looking at the serious adverse reactions thus far, it seems not.

The new buzzphrase that we will have to get used to will be antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Fortunately for Britain, we have our very own UK Envoy for AMR, in the form of Dame Sally Davies, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge—England’s previous Chief Medical Officer, who was responsible for Generation Genome.

What is AMR anyway, and should we be concerned? According to the World Health Organisation, AMR occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and no longer respond to medicines, making infections harder to treat and increasing the risk of severe illness and death. As a result of drug resistance, antibiotics and other antimicrobial therapies become ineffective, making infectious diseases impossible to treat. The world has neglected to research new antibiotics. Is that an oversight or a deliberate omission at a high level?

With no new antibiotics riding to our rescue in this heralded pandemic era, many will find themselves reliant on new experimental heavy-duty cocktails. Those wishing to opt out of the new pharmaceutical armoury that is offered to them will undoubtedly move away from allopathic medicine entirely and opt for alternative naturopathic remedies. New variants of concern, mutants and more virulent viruses will call for super-smart medicine—but not necessarily super-smart patients or super-smart medics.

But ultimately, where does that leave us all? What to expect next—Marburg, polio, typhoid, Ebola, Nipah, or perhaps a combination of several? Could we be about to see the elusive Disease X that experts have been warning of? Time will tell. Pandemics create panic and pandemonium; they can even open Pandora’s box.